OLIVE OIL - NATURE’S ENERGY FLOW

IS THE FUTURE OF MANKIND.

THE PROJECT

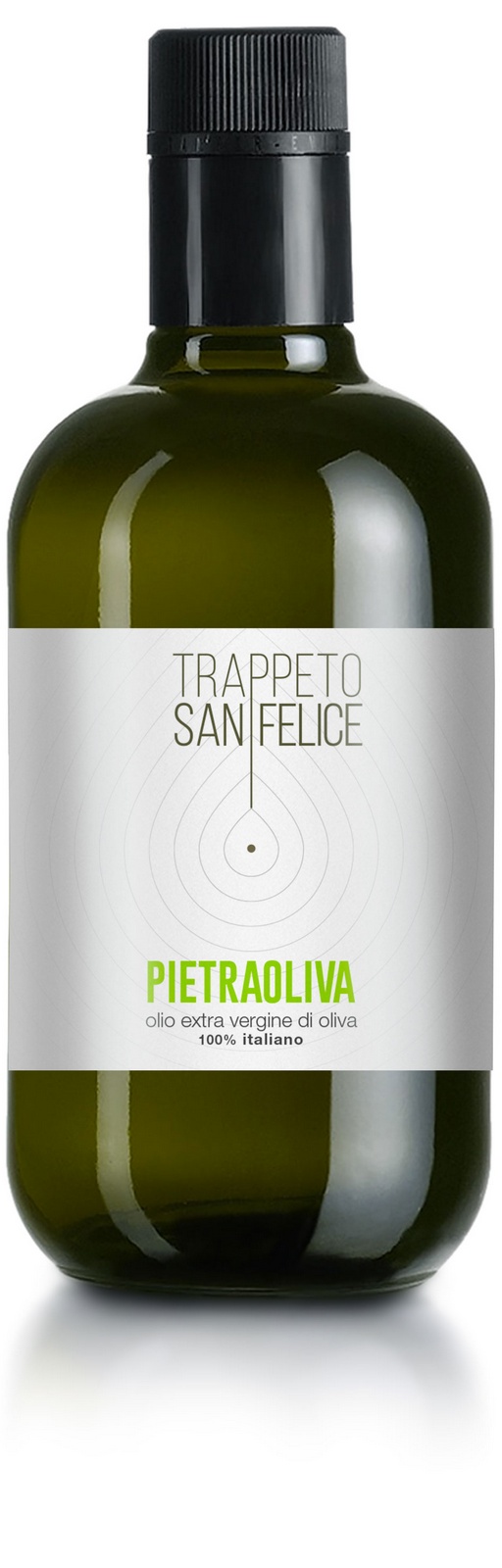

TRAPPETO SAN FELICE is a “young” memory-enhancement

project in the town of Presenzano near Venafro.

It represents a generational

challenge that binds enthusiasm to the bare rock thanks to a love of what is

good and beautiful and the wish to give

new life to the commitment of those who

have gone before us. A rediscovery of tradition in its ceaseless flux of

becoming.

The town of Presenzano

Presenzano lies in an area well known in ancient times for the production of olive oil and trappeti, imposing limestone mills used for pressing olives. The most famous quarry was in Taverna San Felice.

TRAPPETO SAN FELICE is a “young”

memory-enhancement project in the town of Presenzano, near Venafro. It is an

identity-building project, which projects the memory of these places into the

modern world.

In Roman times Marcus Portius Cato, known as Cato

the Censor, mentioned Rufri Maceria (Presenzano) with its oil mills, together

with Pompeii and Nola, among the places in Campania where oil was produced by

artisans. This historic reference confirms the presence and systematic

exploitation of quarries, presumably for the extraction of limestone, as can be

deduced from the surviving remains of the oil presses. The most important was

the quarry of Taverna San Felice, still active today.

The

trapetum

was used to crush the olives during the initial phase of oil production, separating

the stone (

nucleus) and the bitter

liquid (

murca) from the pulp (

sampsa: worked separately using the

torcularium). This was a gentle

procedure: the grinding wheels were fixed “lightly” to avoid damaging the

olives and the ensuing destruction of the

nucleus.

Virgil mentions the

trapetum in his Georgics (II: 519), where he writes: “teritur

Sicyonia baca trapetis

”, meaning “the

olives of Sicyon are crushed in presses”.

Pressing ‘Sicyon’ olives (named after the town

near Corinth) was one of the activities that marked the rhythm of the seasons

for Virgil’s farmer as he worked the fields.

Roman Venafro, just a few kilometres from

Presenzano, boasted a flourishing economy linked to olive trees and their oil, launched,

according to legend, in the 4th century B.C. by Marcus Licinius, a man of

Samnite origin and a citizen of Venafro (hence the botanical name of the Licinian

olive).

Martial too bears witness to the fertility of the soil and the fame of

Venafran oil.

Most of the olive groves are located on the

slopes of Monte Santa Croce, about 400 metres above sea level in Venafro’s “Parco

Regionale Storico Agricolo dell’Olivo”, a protected area.

The

trappeti

not only preserve the mark of the strong, patient, and skilful hands of men, but

they have a spatial dimension more typical of religious buildings, something arcane

and solemn, made up of shadows and silence.

They are obscurely familiar spaces that invite

us to enter and relive them: they were built by fathers thinking of the future

of the generations to come.